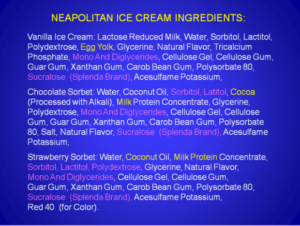

Consider this slide of ice cream ingredients that Dr. Barbara Corkey, director of the Obesity Research Center at Boston Medical Center, used in a recent lecture. The few elements in yellow, she told her listeners, were ingredients that we normally think of as “food.”

There was a collective gasp from her American Diabetes Association audience, and a buzz of distaste. In pink, Barbara went on, were some of the substances she was about to discuss. “Virtually none of these non-food compounds have been carefully assessed for a potential causative or contributing role in the obesity and diabetes epidemic,” she said. In other words, if food additives are insidiously helping to make us fat, we have no way of knowing it.

Her lab is working to change that. It’s still very early days, and some obesity experts are skeptical of her hypothesis, but researchers she oversees are methodically screening hundreds — and perhaps eventually thousands — of food additives, from benign-seeming Bay Oil to unpronounceable chemical compounds, for their potential effects on human fat cells and insulin production. They have already discovered some intriguing leads on possible culprits, including artificial sweeteners, iron and an emulsifier common in dairy products, monoacylglycerols.

Additives, from food coloring to preservatives, have long been a focus of concern. The Center for Science in the Public Interest has a whole glossary called Chemical Cuisine here on the various additives and how harmful they may be. The Center even offers 99-cent Chemical Cuisine apps for iPhone and Android, handy for the supermarket.

Additives must be tested for toxicological safety before they can be put in the food supply, but — as Barbara points out — they are not tested for their effects on our weight or for metabolic effects such as insulin secretion.

Here’s her reasoning: The current explanations of our obesity epidemic are just not fully satisfying. (As a mother who had two daughters who stayed resolutely skinny no matter how she fed them up, she knows how powerful the body’s weight control regulators can be.) So what has changed in the environment over the last generation that might help explain it? Well, one factor — among many — is the dramatic rise in the additives in processed food.

A biochemist, Barbara has developed a model proposing that overactive insulin in the body may be a cause of obesity, as well as a result. So might the food additives, alone or in combination, be affecting people’s base levels of insulin? Might they also affect fat storage, or fat entering the liver?

Dr. Sarah Haigh Molina with some of the food additives being screened

Dr. Sarah Haigh Molina, director of the Boston University High Throughput Screening Core, is tackling that question by testing the effects of a whole “library” of food additives on insulin-secreting cells and on human fat cells harvested from operations.

She can test 40 “plates” a week, of 60 compounds per plate, mixing the food additives in with fat or insulin-producing cells and then checking three days later for effects. Such screening is only a very, very first step — but it points the way toward compounds that deserve further investigation. She hopes to test packaging materials as well — plastics and other compounds that may contaminate food.

Dozens of compounds can be screened on one “plate”

I found myself highly intrigued by Sarah’s work because I, too, find the most popular explanations for the obesity epidemic — we’re just getting less activity and too much food — unsatisfying. But I sought a reality check from the likes of Prof. Marion Nestle of New York University, a leading national expert on nutrition. She sounded skeptical when I asked if there was reason to think additives might play a role in obesity. “If they do, it’s a small effect,” she said by email. “Obesity, alas, is about calories in and out.”

But, I asked, are current explanations for the obesity epidemic adequate? “I’m afraid so,” Marion replied. “There is much evidence that people eat more calories than they need but nobody wants to face that. I am prejudiced, of course, having just written a book about calories in which my co-author and I reviewed the evidence: ‘Why Calories Count: From Science to Politics’ (UC Press, March 2012).”

Michael Jacobson of the Center for Science in the Public Interest sounded similarly skeptical. There doesn’t seem to be any reason to think food additives would promote obesity, he said, and “Food additives go through a lot before they reach fat cells. Some of them aren’t absorbed by the body. Some are metabolized before they would get to the fat cells.”

Like Marion, he said the best explanation of the obesity epidemic is simply that we’re consuming more calories, and if anything correlates best with rising obesity, it’s soda consumption. It seems far from likely “that there’s another major cause,” he said, “although there could be. There’s some evidence that endocrine disruptors could lead to problems. It’s kind of speculative, but there are at least animal studies that suggest that they could be a factor.”

But Prof. Kelly Brownell of Yale University, also a leading national expert and director of the Rudd Center for Food Policy and Obesity, was more enthusiastic: “As far as I know, some people have paid attention to the issue of pesticide use and whether endocrine disruption might be contributing to obesity, but I don’t know that anyone has looked at additives in a systematic way. I think it’s a wonderful idea.”

Many factors contribute to rising obesity, from declining physical activity to relentless marketing by the food industry, he said. But the formulation of food has become a very interesting issue, including portion size and the proportions of sugar, fat and salt in recipes. “People have paid attention to those,” Kelly said, “but there are a lot of things that go into food that haven’t really been studied very much.”

Many common foods have a “mile-long ingredient list,” he pointed out. Sometimes he starts off a lecture by putting up a slide with 50-plus ingredients on it and asking people what food they think it is. They can’t guess. (It’s a chocolate pop-tart.) Some people even question these days whether many products should be called “food,” he said.

Barbara Corkey’s team are not food activists. On the contrary, they caution that their findings so far — which have been presented in public but not yet published — are far too preliminary to influence anyone’s diet. “The last thing I’d want to promote is for people to panic about what they’re eating,” Sarah said. And Barbara recalled that after her June lecture to the American Diabetes Association, people told her they were going to read labels better and stop eating junk. Her response: “Unfortunately, I can’t say this is going to make you any thinner. I hope it will.”

Comments are closed